During 2023, Parishioner Mark Nalevanko shared with us some key figures in church History.

Read more about that here.

In 2024, Mark will be answering “Why Do Catholics Do That?” Questions!

If you have any specific comments, questions, or requests on topics, reach out to Parishioner Mark Nalevanko (mark.nalevanko@gmail.com).

Didache – The Two Ways

Part 2 in Series

In part 1 of this series about the Didache, one of the Church’s most ancient documents outside of the New Testament writings, we offered some historical background and the story of its rediscovery in the 19th century. We now turn attention to its contents, more specifically, the first part known as the ‘Two Ways’. This portion of the document offers us a peek into how the Christian moral life within the early Church was presented to Gentiles.

This part of the Didache, representing chapters 1-6, presents to those catechumens, who are preparing to become Christian and receive Baptism, a choice they must make. “There are two ways, one of life and one of death; but [there is a] great difference between the two ways.” (1) Then a series of ethical pronouncements concerning virtues (good habits) and vices (bad habits) incorporating quotations from both the Old and New Testament are mentioned. Scholars believe that the underlying source for this part of the Didache was a Jewish document that similarly discussed the ‘Two Ways’ with some Christianization added. In Jewish Scriptures (Old Testament) there are repeated references to the two ways. For example, Deuteronomy makes references to a way of blessing for obedience in following God’s commandments and a way of cursing for turning away to other gods. (Deut 11:26-28; 30:15-20) Similarly, Psalm 1 presents a way for the righteous versus a way for the wicked. The Dead Sea Scrolls from the Essenes (1st century Jewish sect) also provide a contrast between a moral way of life versus a way of darkness. (1 QS 3.18-4.26) In the Christian New Testament, the theme continues. As part of the recounting of Jesus’ famous Sermon on the Mount, the Gospel of Matthew (7:13-14) mentions the wide gate that leads to the way of destruction and a narrow gate leading to the way of life. And of course as Christians we believe in Jesus Christ who said “I am the way, the truth, and the life.” (John 14:6)

The ethical pronouncements of chapter 1 are initially centered on the Golden Rule of loving God and neighbor. References to New Testament teachings are clearly made including a love of enemies (but admonish them when necessary), offering the other cheek, and giving generously without expecting anything in return. (Matt 5:38-6:4; Luke 6:27-36) Chapter 2 then presents several commandments in the mold of the Ten Commandments, including ‘you shall not commit murder’, ‘you shall not commit adultery’, ‘you shall not steal’ and ‘you shall not bear false witness.’ However, this chapter expands upon these commandments by applying them to some specific situations too, most notably, “You shall not practice magic. You shall not practice witchcraft” and “You shall not murder a child by abortion nor that which is begotten.” (2.2) So while some critics may claim that the Scriptures do not explicitly mention anything about abortion, we have here the oldest known explicit Christian prohibition of abortion in writing. Chapter 3 goes on to expound upon the avoidance of bad behavior that leads to sin, such as anger leading to murder, lust leading to fornication and adultery, superstitions leading to idolatry, lying leading to theft, and grumbling leading to blasphemy. On the other hand, one should develop good qualities including meekness, humility, patience, and gratitude.

Chapter 4 also offers a contrast between desirable behaviors, such as offering proper respect and attention to the teachers of the Faith, serving as peacemakers, and judging justly, versus improper behaviors, such as always receiving, but not giving. It is worth highlighting two other things mentioned within this chapter. One is the important parental role of teaching the Faith to one’s children. The other is the precept “in the church you shall acknowledge your transgressions, and you shall not come near for your prayer with an evil conscience”. While scholarly debates exist over what this confession of sins (and the repentance process associated with it) exactly looked like in the early Church, one can clearly see how this practice exists within the modern Church through the Penitential Act, which is performed at Mass immediately after the initial greeting. This act is for the remission of venial sins and it is most commonly presented as a short litany where the congregation responds “Lord, have mercy; Christ, have mercy; Lord, have mercy” but may also take the form of the Confiteor when we say:

“I confess to almighty God and to you, my brothers and sisters, that I have greatly sinned, in my thoughts and in my words, in what I have done and in what I have failed to do, through my fault, through my fault, through my most grievous fault; therefore I ask blessed Mary ever-Virgin, all the Angels and Saints, and you my brothers and sisters to pray for me to the Lord our God.”

Chapter 5 essentially reiterates that failure to keep the previously mentioned precepts will lead to the way of death. Finally, chapter 6 turns attention to being vigilant against letting others turn you away from the way of life. It concludes with a somewhat interesting comment about food, mentioning that one should abstain as much as you can, in particular avoiding anything given as sacrificial offerings to idols. It is not clear exactly what is meant here with regards to abstaining in general. Is it for certain foods such as dictated by Jewish laws, or all meat, or a limitation of quantity? Is it in reference to what can be eaten on certain days of fasting, such as Wednesdays and Fridays, which are detailed a bit more in a later chapter of this document? In any case, it was clear that the early Church had to address and combat the common societal practices of offering food to various pagan gods.

In the next part of this series on the Didache, we will look at the second section (7.1-10.7), which centers on Liturgical practices surrounding Baptism and the Eucharist.

Didache

Rediscovering a Long Lost Early Church Document

Part 1

If you ask most Christians, including many Catholics, if they’ve ever heard of the Didache (pronounced DID-uh-kay), the likely response more times than not might be “say what?”, that is if you get anything more than a blank stare. Fear not! With this first part of a multi-part series, we will dig into the fascinating history, rediscovery, and significance associated with one of the earliest written Church documents outside of the books of the New Testament. This document served two very important roles within the early Church: a catechism and Church manual. It also points clearly to several long held Church Teachings and Traditions. Read on to learn more.

The word Didache is a Greek word and means “teaching”. It is the shorthand title for an early Church document that initially begins with the line “The Lord’s Teaching Through the Twelve Apostles to the Nations”. Scholars believe it was formulated during the first century AD or at the very latest during the first part of the second century. At a high-level, the document is about as long as St. Paul’s letter to the Galatians with roughly 2500 words. It contains four primary parts that are spread across 16 chapters: a catechesis leading towards Baptism, Liturgical procedures regarding Baptism and the Eucharist, church rules and order, and some eschatological (i.e. end times) points. Scholars believe that this document served as a means for presenting the early Church’s teachings to Gentiles (non Jews). Before reviewing the sections of this document in more detail and highlighting the teachings and practices from it that continue in the modern Church (more on that in subsequent articles), this article will focus mostly on the Didache’s historical usage and rediscovery story.

References to the Didache occur from several surviving sources of the early Church. Bishop and Church historian Eusebius of Caesarea (260-339) lists it within his lengthy compilation known simply as Church History, which was written around the early 4th century. Eusebius mentions the document as being known by many and while he did not himself include it as part of a canon of Scriptures, there was a debate over whether it should belong or not (Church History, 3.25.6). Similarly, St. Athanasius of Alexandria in writing about a canon of Scriptures in 367 also mentions the Didache by stating that while it is not in the canon it is a valuable resource for those looking to learn the Faith. Later writings would incorporate parts of the Didache, such as the Didascalia (probably originated in Syria in the mid 3rd century)and Apostolic Constitutions (probably also from Syria around late 4th century), both of which fall into the same general category of Church Orders aimed at providing guidance on moral living along with Church liturgy and organization.

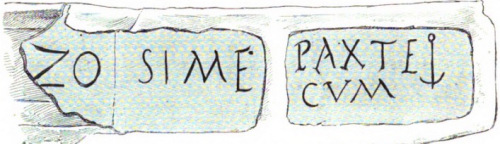

The Didache ultimately was not officially recognized by council decree in the canon of Scriptures by the Catholic Church towards the end of the 4th century. This decision was likely the result of the document being primarily a Church manual focused on addressing practical matters within a certain locale. Subsequent Church manuals like the Apostolic Constitutions also likely pushed the memory of the Didache further and further into the past. For many centuries, manuscripts were presumed lost. Then in 1873, an almost complete Greek text of the Didache surfaced within a manuscript of several early Church writings discovered in the library of the Holy Sepulcher in Constantinople (present day Istanbul, Turkey) by Byzantine bishop Philotheo Bryennios. The manuscript was dated from 1056 and also included letters from Pope Clement I (r. 92-100) and St Ignatius of Antioch (d. 107) among others. While this particular copy of the Didache represents the most complete version we have today, the copyist who wrote the manuscript left space at the end of it under the correct assumption (based on subsequent manuscript findings) that he knew that the source he was copying from was not entirely complete.

In the early 20th century, an additional partial Greek manuscript of the Didache was uncovered from a set of manuscripts discovered in Egypt. This version was dated to around the end of the 4th century, the earliest known existing manuscript of the Didache! (See picture of a fragment from this manuscript). Around the same time a Coptic (Egyptian language) version dated from the beginning of the 5th century was also discovered in Egypt. While only containing a portion of the Didache (typically numbered as 10:3b-12:2a), this version makes reference to the offering and blessing of oil at Mass, serving as one of the first references in Church documents on how oil intended for healing purposes was specifically blessed in a liturgical act, which carries to the present day at the Chrism Mass when the bishop blesses the oils to be used for the Sacraments within a diocese. Additional versions of the Didache written in Ethiopian and Georgian have also surfaced.

With these discoveries within the past 150 years, the Didache’s significance within the early Church has been reconsidered. While many questions remain over its exact origins (time and place), its contents offer a unique glimpse into what Church life looked like in the early Church. More on that in subsequent articles.

Jubilee Year 2025

History and Significance

As we approach the end of one calendar year and the start of a new one, we will be entering a specially designated year for the Church called a Jubilee Year. But what is the significance associated with this designation and how did it become a tradition in the Church? Read on to learn more.

A jubilee, like many aspects of the Christian faith, has its origins from the Jewish faith. Leviticus 20:10 reads “And you shall hallow the fiftieth year, and proclaim liberty throughout the land to all its inhabitants; it shall be a jubilee for you, when each of you shall return to his property and each of you shall return to his family.” In other words, every fiftieth year (ie: the year after every seventh sabbath year; a sabbath year occuring once every seven years) was a time for slaves to be freed, leased property returned, and all debts to be forgiven – a universal pardon of sorts – in recognition that ultimately all things belong to God.

In Catholic tradition, the significance of 50 years carried on, albeit not in a defined manner applicable to the Universal Church for several centuries. Some early reports suggest there was a custom for monks and nuns to celebrate a jubilee year after 50 years of making their professions. Likewise special memorials marked the 50th year after the death of certain saints. The idea of a jubilee as designating a year focused on the forgiveness of sins and the punishment associated with those sins is first documented around 1300. During a time of war, poverty and pandemic, Pope Boniface VIII officially designated the first “jubilee” year while also decreeing that one should be held every 100 years. The pope’s decree did not use the term “jubilee,” describing it as a “holy year” instead, but “jubilee year” became associated with the celebration through other writers. The focus of the year was on confessing one’s sins while undertaking a pilgrimage to Rome, visiting the basilicas of St. Peter and Paul for a number of days during the year as part of gaining a plenary indulgence. With people liking the jubilee idea so much, it was only a few years later that Pope Clement VI decided to make the jubilee year an every 50 years occurrence before eventually a tradition of typically every 25 years was established by the late 1400s, which continues to the present day. Although, there have been exceptions. For example, Pope Francis designated 2016 as an extraordinary jubilee of mercy with its opening day of December 8, 2015 coinciding with the fiftieth anniversary of the closing of the Second Vatican Council in 1965. Pope Francis also introduced the idea of a diocesan Holy Door with that particular jubilee. The tradition of opening “Holy Doors” for pilgrims to pass through began in 1500. The passing through the doors served as a symbol of the interior conversion of a believer and a reminder of Christ’s admonition to “knock, and the door shall be opened unto you” as one entered into communion with fellow believers.

The 2025 jubilee’s theme is “Pilgrims of Hope”. While diocesan Holy Doors will not be a feature of this upcoming jubilee year, the four Papal Basilicas in Rome – St Peter’s, St. John Lateran, St, Mary Major, and St. Paul Outside the Walls – will have their Holy Doors open. The jubilee year kicks off on Christmas Eve with the opening of the Holy Door of St. Peter’s Basilica (see picture) and concludes with the closing of that same door on January 6, 2026, the Feast Day of the Epiphany. There is a website with more information on the jubilee available at https://www.iubilaeum2025.va/en.html

Dogma vs Doctrine vs Discipline vs Devotions

So many D’s! What do they mean and how are they different?

It is not uncommon for Catholics to get accused of having to follow “too many rules” or participating in “weird traditions” from those that don’t really understand the meaning or purpose behind it all. It may be that some Catholics don’t really know much better either. In large part the ‘Why Catholics Do That’ series here has been written toward trying to offer some brief background on many Catholic practices and beliefs. This latest article will attempt to briefly explain a broader topic concerning the 4 D’s of Catholicism – Dogma, Doctrine, Discipline and Devotions – which usually are at the crux of understanding the bigger picture when it comes to what Catholics believe and do, whether they require assent by the faithful, and whether they are changeable. Read on to learn more.

Doctrine constitutes the body of teachings of the Church on matters of faith and morals that all members are to definitively assent to. When attempting to define what is Doctrine, it is common to also throw in the term Dogma. Sometimes these words get used interchangeably, which can be a bit misleading. Dogma is really a subset of Doctrine, which has been elevated to a special status through a declaration by the Church confirming its unchangeable truth from divine revelation. As stated in the Catechism of the Catholic Church, “The Church’s Magisterium exercises the authority it holds from Christ to the fullest extent when it defines dogmas, that is, when it proposes, in a form obliging the Christian people to an irrevocable adherence to faith, truths contained in divine Revelation or also when it proposes, in a definitive way, truths having a necessary connection with these.” (88) It has been the mission of the Church’s bishops to subsequently hand down all Doctrine through the centuries to the present day. During the course of that process, they can certainly help better explain Doctrine, known as the “development of doctrine,” but no fundamental change is to occur. This process is most typically demonstrated when battling against a heretical movement, which oftentimes lead to a dogmatic declaration too, thus elevating a Doctrine to Dogma. Some examples of dogma are the divinity of Christ, the Real Presence in the Eucharist and the Immaculate Conception of Mary. Some examples of Doctrine include the priesthood being reserved only for men and the events of Christ as recorded in the scriptures, such as the Resurrection and Ascension.

On the other hand, Discipline is instruction that is man-made under the authority of the Church. As scripture states, the Church’s leadership was also given authority to enact discipline: “Whatever you bind on earth shall be bound in heaven, and whatever you loose on earth shall be loosed in heaven.” (Mt. 18:18) Within these man-made constructs though, there is always the possibility for change, especially in consideration of new and different circumstances and situations that arise. Some examples of Discipline are the specifics of what is said and done during Mass, how the Lenten fast is undertaken, and priestly celibacy – all of which have varied during the course of the Church’s history. With that said, Catholics are to assent to the current disciplinarian practices of the Church.

Admittedly, it can be confusing how to classify everything mentioned in the Bible. If one takes a strict sola scriptura approach where everything in the Bible is to be taken as doctrine, one can quickly run into situations where women are never to speak in the church (cf 1 Cor 14:33-35) or wear anything in a decorative fashion like hair or jewelry (cf 1 Pet 3.3) and must wear a veil while praying (cf 1 Cor 11:5-6). Even a careful look at the rulings from the Council of Jerusalem mention that Christians should never drink blood (anyone have a medium or rare steak?) or the meat of a strangled animal (cf Act 15:28-29). As one can see, the task of discerning through these details can be daunting and is ultimately a task for the Church’s Magisterium – thank God! All of these examples fall under the category of Discipline and have changed through time.

Lastly, there is a category known as Devotions, which represent pious practices of the faithful that aid in one’s faith journey. However, there is no required obedience of faith involved with them. Many of these have been mentioned as part of previous articles. Examples include the usage of various items such as holy water, candles, and incense, and various forms of prayer, such as the rosary and the stations of the cross.

Relics – A Way To Remember

The Church has had a long history when it comes to venerating objects as a means to recall specific events and honor individuals. Even within pop culture there have been movies produced and books written centered on some of these items: the Ark of the Covenant and the chalice used at the Last Supper are two very famous examples. There have been first-class, second-class and even third-class classifications of these items and more recently significant and non-significant relic classifications. Over the centuries opponents to the Church have accused Catholics of idol worship surrounding this practice too. How do we make sense of it all? Read on to learn more.

First a quick overview of some of the nomenclature. Up until 2017, there was a three-tiered classification system within the Church. First-class relics were the body or some part of the body of a saint. Second-class relics were objects closely associated with a saint, perhaps an article of clothing or some other personal belonging. And lastly, third-class relics were any objects that touched a first or second-class relic. However, as one might imagine, the classification of third-class relics was rather broad and consequently became an area of abuse and a even a source for jokes as people claimed certain items or even themselves to be third-class relics for having shook the hand of a person who later became a saint or touched another relic associated with a saint. In 2017, the Congregation for the Causes of Saints, which is also responsible for deeming the authenticity of relics, abolished the third category while introducing the language of significant and insignificant relics. As one may rightly suppose, significant relics represent the full body (see the picture of the incorrupt body of Padre Pio – feast day Sept 23 – as one example) or significant parts of the body of a saint (or their ashes) while insignificant relics refer to small fragments of bone and objects associated with the saint.

With Scripture as its basis, the Church from its beginning has assigned great importance to the body. After all, the body along with the soul is what constitutes a human person. Exodus 13:19 sets the tone for the reverence owed to the body even after death when Moses and the Israelites took the bones of Joseph with them as they fled Egypt. In Genesis 50:22-26, Joseph himself had made this request as he neared the end of his life on earth. As mentioned in the Catechism of the Catholic Church, burying the dead is a corporal work of mercy (CCC 2300). Also in the Old Testament, we see in 2 Kings 13:21 the potential power manifested through the body even after death when a dead man was brought back to life upon touching the prophet Elisha’s bones. In the New Testament we also see from Acts 5 and 19 respectively the healing powers coming forth from the body and objects closely associated with a person’s body. People were healed by Peter when he cast his shadow on them and Paul sent articles of clothing to be used for healings. Jesus also healed on several occasions as people touched his clothes, perhaps none more well known as the woman who suffered from bleeding for many years as written in Luke 8.

The early Church Fathers were unanimous in the approval of the veneration, but not worship, of relics. The first still extant documentation of the collection of relics in the early Church is associated with the martyrdom of St. Polycarp, who was burned at the stake (or more accurately had to be pierced with a sword when the flames would not burn him) around AD 156. His bones were preserved and treated as “more valuable than precious stones and finer than refined gold.” Oftentimes the early meeting places for the Church were at the tombs of martyrs too. The Second Council of Nicaea in 787 decreed that relics should be used to consecrate churches, a practice that had already existed for centuries at that time and continues to the present day. As part of consecrating a church, the relics of one or more saints are entombed under the altar. As noted by St. Ambrose in the 4th century, the practice was done to give honor to those who had been redeemed by the sufferings of Christ.

Throughout the Church’s history there have been countless miracles associated with relics. While there will be detractors of this practice of the Church, one has to keep in mind that relics are always to be venerated and never worshiped. Only God deserves worship.

Gold – Meaning and Usage in the Church

In today’s world we probably think of wealth and riches when we hear the word gold. However, in ancient times, the metal took on another meaning primarily with its association to divinely or sacred things. The Church ultimately carried on this tradition to the present day with some twists and turns along the way. Read on to learn more about how the story of gold and its usage by the Church unfolded.

As perhaps demonstrated no more apparently than from the excavated tombs of the pharaohs, ancient Egyptian culture reserved gold for items that were used to convey either the pharaoh’s status as being an incarnate god or to represent other Egyptian gods. Beyond its use in some jewelry, it was not used as a currency. Gold, which is known for its resistance to tarnishing and corroding, was instead associated with the divine quality of immortality and was often described as “the skin of the gods”. Items used for ritual ceremonies associated with the worship of the gods were also made of gold.

The Israelites continued these customs as part of their initial acceptance of the covenant with God. Shortly after the flight from Egypt while at Mt. Sinai, the construction of the Ark of the Covenant occurred. Even though the Ark was built from acacia wood, gold was overlaid both within and without in addition to a gold mercy seat and gold cherubim on top. Gold rings and poles overlaid with gold to facilitate carrying the Ark were also constructed (see Ex 25:10-22). Given the nation of Israel’s experience living within Egyptian culture, it may be little surprise also to find that when they fell away from God while waiting impatiently for Moses as he conversed with God on the mountain, they constructed an idol with gold (golden calf) as an attempt to represent the gods that led them out of Egypt. Later on when a united Kingdom of Israel was firmly established, King Solomon constructed the first iteration of the Temple using gold to overlay the Holy of Holies room where the Ark of the Covenant resided. Additionally many vessels and objects residing within the Temple were made of gold (see 2 Chr 3-4).

The early Church continued this practice of associating gold with Christ’s presence in the Eucharist. However, it was not easy to acquire gold objects. Consequently, the first chalices and patens (dishes for the bread) during the time before the Christian Faith became legal in the Roman Empire in the early 4th century were likely made of the most durable material that could be acquired at the time, such as wood, metal, glass or clay. There is some record of a preference given to glass for the paten and chalice early on perhaps in enabling the congregation to more easily see the Body and Blood of Christ. Pope Zephrynius (r 199-217) is recorded in the Liber Pontificalis (Lives of the Popes) as calling for the use of “vessels of glass before the priests in the church”. However, it’s probable that the fragility associated with glass prompted Urban I (r 222-230) to call for sacred vessels to be made of silver just a few years later. This did not exclude the usage of gold though if a congregation could procure. An inventory of seized Church property around AD 303 during the persecution under Emperor Diocletian from a Church in Algeria included two gold chalices and six silver chalices among several other items.

With the legalization of the Faith in the 4th century and the wealth donations from emperors and other high-society individuals, gold vessels became much more common with sophisticated ornamentation involving gemstones too. One example as shown in the picture is the Chelles Chalice which is believed to have originated during the 600s but was lost at the time of the French Revolution. Gold became integrated in other Church objects as well including altars, artwork (including the depiction of saints with their golden halos), books, and vestments. As congregation sizes grew, a pragmatic issue surfaced over how best to distribute the Blood of Christ as the initial custom was to share a single chalice. Some chalices grew in size to contain handles and hold enough liquid as a 2 liter soda bottle! Some of the solutions that came out of this situation still manifest themselves today. One was intinction, where the host is dipped into a chalice or soaked and then distributed by the priest using a spoon. This practice is employed by some of the eastern Rites of the Church. Another was simply to use more chalices. Another was to not distribute with the chalice given the Church’s understanding that Christ is fully and truly present in either the host or the chalice. This ultimately became the more typical tradition in the West around the 12th century and after. In the West the chalice used by the priest during consecration ultimately became smaller to what we typically see today. Similarly, the paten of the early church was also very large with some reportedly donated by Constantine the Great as being made of gold and weighing around 8 pounds! Over time this changed to where the paten became smaller too with its function being to hold a single large host used during consecration by the priest while ciboriums containing several small hosts were used for distribution.

Today, each bishop across the dioceses of the United States has the discretion to permit and/or promote the distribution of both species of the Eucharist. In the diocese of Raleigh the decision is given to the pastor of each parish to make. The General Instruction of the Roman Missal contains in numbers 327-334 the current requirements for sacred vessels. In a nutshell, the intent is that they be made from a non absorbent material commonly deemed as precious within each region and not from items that are prone to breaking. Consequently, there is room for some variation although in most cases a preference to gold is given due to its longstanding association with divinity.

Eucharistic Adoration

With the recent three year National Eucharistic Revival period led by the US Bishops focused on reviving the Catholic understanding of and devotion to the Most Holy Eucharist, it is worth taking a look at how the practice of Adoration developed through the Church’s history. It is not simply a form of pious eccentricity, but based on revelation and Catholic doctrine. Even though the recent Eucharistic Revival period officially came to a conclusion with the Eucharistic Congress over July 17-21, 2024 in Indianapolis, IN, we are called to continue this most important and ancient practice within the Church. Read on to learn more.

The custom of preserving the Eucharist is documented going back to around AD 120 through the practice of fermentum, or “leaven of unity”, whereby some of the Eucharistic bread was carried on behalf of the bishop from one diocese to the bishop of another diocese. The receiving bishop would then consume the species at Mass as a sign of unity amongst the churches. This practice of fermentum combined with reserving the Eucharistic for the sick and the dying led to the custom of the Blessed Sacrament’s presence as part of the the structure of a church, especially within monastic communities, where monks would carry the Eucharist with themselves as a means to provide Communion to others and as protection during travels. In the 4th century, documentation exists of St. Basil the Great dividing the Eucharistic into three parts when celebrating Mass at a monastery. One part was consumed, another given to the monks, and the third part in a golden dove, a precursor to modern day tabernacles, suspended over the altar. It was within these early monastic communities that an early form of Perpetual Adoration began with some communities such as the Acoemaeta, or “sleepless monks”, of the Eastern Church holding an endless divine liturgy day and night starting in the 5th century whereby groups of monks would rotate their attendance for liturgy around the clock. It is also believed that in the late 6th century a perpetual adoration of the Eucharist began in Lugo, located in NW Spain, which continues to this very day!

For the first approximately 1000 years, the belief of the Real Presence was a given within the Church. However, a French deacon named Berengar of Tours (999-1088) began promoting the denial of transubstantiation, which states that Christ’s real presence exists under the species of bread and wine after consecration in the Eucharist. His actions prompted Pope Gregory VII to issue the Church’s first definitive statement on the Real Presence in the Eucharist, essentially a clarification on the doctrine of transubstantiation. Additionally, these events sparked the period’s own Eucharistic Revival with formalized processions and acts of adoration legislated and Adoration within monastic communities especially emphasized. After victory over the Albigenses, King Louis VII of France asked that the Blessed Sacrament be exposed in the Chapel of the Holy Cross in Avignon starting on September 14, 1226. The adoration ultimately continued uninterrupted day and night until the French Revolution in 1792 before resuming again in 1829! (Note: As an interesting side story, this chapel was also the scene of a miraculous event whereby the Eucharist was protected from a flood event on Nov 30, 1433, the Feast Day of St. Andrew, where it was reported that the central aisle and altar were protected by a parting of the Red Sea type event despite the flood waters being halfway up the front doors of the Church!) The movement also led to Pope Urban IV’s instituting of the Feast of Corpus Christi in the 13th century, the first papally imposed universal feast of the Latin Church. The feast’s focus is on celebrating the real presence of Christ in the Eucharist.

For the second millennium of the Church, recurring heretical beliefs would occur, highlighted in particular by the Protestant Revolution of the 16th century with various Protestant denominations eventually offering different takes on whether or not or how the Real Presence existed in the Eucharist. It was in 1592 that Pope Clement VIII issued a document called Forty Hours, which formally established across the Universal Church a devotion that was initially local to the area of Milan involving forty hours of prayer before the exposed Blessed Sacrament. Some religious institutes, beginning with the Benedictines of the Perpetual Adoration of the Blessed Sacrament (1653) and the Sisters of the Blessed Sacrament and Our Lady (1659), along with Eucharistic associations also formed dedicated to Perpetual Adoration. The groups have grown in the centuries since. And it was in the 20th century that the practice of perpetual adoration spread into Catholic parishes at large. St Pope John Paul II inaugurated a perpetual adoration chapel in St. Peter’s Basilica in 1981. Today, a perpetual adoration chapel at a parish must be approved by the local bishop. There are currently around 1,100 perpetual adoration chapels at parishes across the US. In the diocese of Raleigh, the closest one to St. Andrew’s is at Our Lady of Lourdes in Raleigh. While typically people will sign up for an hour at a time for Adoration, there are no set rules on how long or what exactly should be prayed while attending. Some will say specific prayers like the Rosary and/or read Scripture, while others will simply sit in silence with the Lord. St. Pope John Paul II was known for spending a couple hours daily in an Adoration Chapel using the time to write.

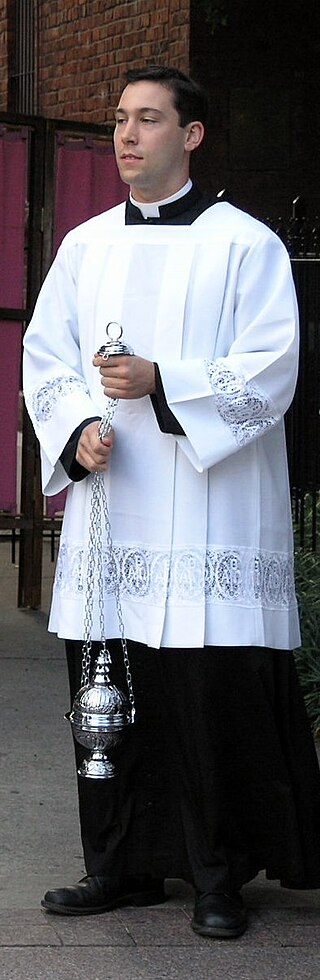

The process of beginning or concluding Adoration is usually performed by a priest or deacon but it is permitted in their absence for a designated member of the laity to perform these duties including the opening of the tabernacle, placing the ciborium on the altar and putting the host in the monstrance for display (see picture) but without giving the blessing or using incense. The lay minister typically wears something fitting of altar service work, such as an alb, but does not use the cope or humeral veil (see picture) that is worn by clergy as part of the exposition and benediction of the Blessed Sacrament.

With that all said, it is worth noting that Adoration is not a substitute to the Mass, which is our obligatory communal celebration of the liturgy. However, Adoration serves as an important means to extend our union with Christ. If you are not familiar with attending Adoration, consider giving it a try! It’s a great way to take some time away from the business of daily life and spend it with Jesus. At St. Andrew’s Adoration is offered on the first Friday of each month (excluding July typically) from 10AM to 9AM the following Saturday.

1 – Order for the Solemn Exposition of the Holy Eucharist, The Liturgical Press, Collegeville, Minn, © 1992. no. 26

2- Ibid., no. 6

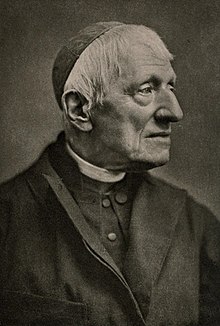

Why are Catholic Centers at Universities often called Newman Centers?

John Henry Newman – Remembering the Churchman and Scholar

Most famously known for his conversion from the Church of England to Catholicism in the mid 1800s and his name’s association with many Catholic campus ministries at universities across the United States, there is certainly more to know about the life and teachings of John Henry Newman, who was recently canonized a saint by the Church in 2019. While his feast day is on October 9, the day of his conversion to Catholicism, Newman died on August 11 in 1890 (and is still recognized with a feast day on that day in the Church of England), so it is an appropriate time to recall this saintly churchman and scholar.

Born to a London banker on February 21, 1801, Newman was the oldest of 6 siblings. From a young age he took to reading books as his first pastime. At the age of 15 he entered Trinity College, one of the constituent colleges of Oxford University. Known as an over-worker and over-worrier, Newman completed a Bachelor of Arts in 1821, but only with very average accolades as he succumbed to some of his self-imposed pressure in completing his studies. However, he went on to hold a series of teaching positions at Oxford while also becoming an ordained Anglican priest in 1825. He was described by one Anglican colleague as “one of the acutest, cleverest, and deepest men” he had ever met.

During his teenage years he placed a premium on dogma as the fundamental principle for religion as opposed to any sort of sentimentality. This underlying premise provoked Newman to be involved in what became known as the Oxford Movement led by those in the Church of England who desired more emphasis on the rituals, priestly authority, and sacraments, aligning more closely with the heritage of the Catholic Church. It also led to the establishment of Anglican religious orders for both men and women. Ultimately, Newman along with several other authors began publishing a series of writings known as the Tracts for the Times. Supporters of these publications, known as Tractarians, aimed to secure both the doctrine and discipline of the Church of England. They also claimed Anglicanism formed one of three branches (Roman Catholicism and Eastern Orthodoxy being the other two branches) from the pre-schism Catholic Church. In Tract 90, Newman reconciled the Catholic doctrines of the Council of Trent with the Thirty-Nine Articles proclaimed by the 16th century Church of England, which created a firestorm of ridicule directed at him by some fellow Anglicans. For Newman, it increasingly became apparent that there were flaws in the “branch theory” approach and that Anglicanism was not on a path at the time leading back fully to Catholicism. He spent time trying to make sense of some of the historical contrasts between the early Church and the modern Roman Catholic Church. Eventually Newman was received into the Roman Catholic Church on October 9, 1845. Shortly after came the publication of one of his most well known books, An Essay on the Development of Christian Doctrine, which outlines how Catholic teaching has developed, but not changed, over the centuries by way of becoming more detailed and explicit through the application of reason to revealed truths.

Newman’s admission into the Catholic Church caused a lot of personal heartache with broken relationships with friends and family. However, he persevered and became ordained a Catholic priest in October 1846 and became an Oratorian (founded by St. Philip Neri) before returning to England in 1847. He continued to serve in teaching/education roles throughout the remainder of his life and would later on publish a number of works, including an autobiography called Apologia Pro Vita Sua, which more thoroughly explained his decisions to convert and seemed to temper some of the outrage directed toward him.

The first “Newman Club” focused on bringing together Catholic students at secular universities to share their faith and socialize was established at Oxford University in 1878. It was later renamed the Oxford University Newman Society in 1888. The first Newman Club in America was established in 1893 at the University of Pennsylvania. Today, there are over 2,000 Newman Centers across the US.

In 1870, Newman published Grammar of Assent, which like his earlier book on the development of Christian Doctrine focused on the interplay of faith and reason. While Newman was made a cardinal by Pope Leo XIII in 1879, he was never consecrated a Catholic bishop, at his own request and not a requirement to be a cardinal even though in most cases bishops are chosen to be cardinals. Newman’s health began to start failing in 1886 and he died on August 11, 1890.

Interestingly as part of the canonization process for sainthood, Newman’s remains were exhumed in 2008, but no bones were found! While there appears to be a scientific explanation given the manner and environment in which his remains were placed, it seems a bit apropos given that Newman’s patron saint St. Philip Neri (1515-1595) had a saying “to love to be unknown.” In his pursuit of living a scholarly life in the Faith, Newman was known as one who especially strove to embrace the virtue of humility. He is sometimes called the patron saint of Ecumenism and since his time ongoing efforts for full communion between the Church of England and the Catholic Church continue. One noteworthy step was the 2011-12 establishment of Anglican Ordinariates in Great Britain, Australia, and the US, which permitted groups of Anglicans and Methodists to join the Catholic Church while still preserving elements of their liturgical heritage.

Priestly Vestments – Making Sense of It All

From the simple everyday black outfit with white collar to the more ornate vestments worn at Mass, most Catholics likely take for granted the various attire worn by priests. However, have you ever really thought about what it all signifies? And where did these customs come from? Can and do they change? Read more to learn more.

While a description of the first priestly vestments is detailed in Exodus 28 at the time when Aaron (Moses’ brother) and his sons of the tribe of Levi were designated as the first priests of the Israelites, the vestments employed by the early Christian Church initially followed the everyday garb of the Greco-Roman world, which primarily consisted of a tunic and a cape-like outer piece of clothing called the mantle. This was likely done in part by practicality so as not to draw unnecessary attention to individuals during a time when the Faith was not legally permitted. While common dress was employed, there was an emphasis on making sure the clothing was kept very clean when performing liturgical duties as exemplified with a ruling from Pope Stephen I in AD 225 stating that “priests should not use their consecrated garments for daily wear, except in the church.” The tunic was initially made of wool but then linen by the 3rd and 4th centuries. The tunic began to fade away from everyday garb around the 6th century. However, the Church continued to use it to the present day in a form known as the alb, the long-sleeved, ankle long white robe worn by priests for liturgical ceremonies under other outer garments. Altar servers may wear the alb as well or a variation known as the surplice (see picture) which consists of wide sleeves and goes down to about the knees versus the ankles.

It is also around the 5th and 6th centuries that we see the establishment of both the pallium (see picture) and the stole as part of liturgical wear. The pallium is a narrow three-finger shaped adornment. While initially worn by bishops, especially in the East, in its earliest form, and intended as a symbol of the Good Shepherd carrying a lamb over his shoulders, this vestment is now mostly associated with the pope. The stole, a narrow band of cloth, is worn both by priests, over both shoulders, and deacons, over the left shoulder, and matches the liturgical color of the day (more on that shortly). A cincture, a cord/belt, is used to keep the alb and stole in place.

The final outer garment, known as the chasuble, completes the typical liturgical outfit for priests. It’s essentially a cloak that matches the liturgical color of the day. While the decor of the chasuble at one point during the Church’s history became very elegant, a more simple trend pervades in modern times. Deacons also wear something similar to a chasuble, but it is called a dalmatic.

The color of the outer garments will depend on the liturgical day. Ordinary time, which makes up most of the year, is green, the color of life and hope. White, the color of purity, is used during the seasons of Easter and Christmas. It is also used on feast days of Our Lord not associated with the Passion and other saints who were not martyred. Red as a symbol of blood is used on feasts associated with Christ’s Passion and martyred saints. Purple, or more technically violet, the color of penance and mourning, are associated with the Lenten and Advent seasons. There are also two special occasions whereby rose colored vestments are used as a symbol in tandem with the Scripture message to rejoice as proclaimed on the third Sunday of Advent and the fourth Sunday of Lent.

It was not until around the 16th century that an everyday outfit for clergy evolved into wearing a cassock, another successor to the tunic from Greco-Roman times, which featured a rigid high collar too. It was not until 1884 that the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops mandated that priests wear a black outfit with white collars when not performing liturgical functions. Around this time, the detachable collar became prevalent. The collar symbolizes a number of things. Beyond being simply a visual means of distinguishing the clergy from others, it also represents both the commitment made to God by the individual and his submission in service to God and Church.

Now that you’re familiar with these items you can go up to the priest after Mass and say “Nice chasuble!” and similarly to the deacon, “Nice dalmatic!”

Fasting – Origins – History – Present

Fasting has been a common practice of the Church since its foundation and part of Judaism going back much earlier. However for many modern-day Catholics it has likely become a practice mostly associated only with the Lenten season or perhaps as part of going on a “diet”. With the emphasis these days on living comfortably and obtaining fast results, the role and true meanings behind fasting can often be diminished or overlooked. But, like most everything within the Church, there are biblical and practical considerations along with traditions to be understood. To learn more about the role of fasting through the Church’s history read more here.

The Old Testament points to the role of fasting as an important part of Mosaic Law in Judaism with the Day of Atonement (Yom Kippur) designated specifically as a fasting day (Lev 16:29-34; Lev 23:27; Num 29:7) (Note: Many bible translations will use the terminology “afflict” or “deny” oneself as a reference to abstaining from food among other things too.) Additional references are also made to other occasions where fasting is employed, such as repentance (1 Sam 7:6; Joel 1:14; Jonah 3:5-9), supplication in time of calamity (2 Chr 20:3-4; Ezra 8:21-23), mourning ( 2 Sam 1:12, Nehemiah 1:4) and as a spiritual preparation for an undertaking, such as Saul’s army preparing for battle (1 Sam 14:24), or as Moses and Daniel sought guidance from God (Exodus 34.28; Daniel 10:2-3).

The New Testament also mentions fasting in various capacities. Jesus prepared for his public ministry by embarking on a forty day fast (Matthew 4:2; Luke 4:2). While fasting by his disciples was not something purposefully done, and sometimes asked about by others in a somewhat critical manner, Jesus did foretell of its role when He would no longer be with them (Matthew 6:16-18; Mark 2:20). Paul utilized fasting as a spiritual preparation, both prior to baptism (Acts 9:9) and towards the selection of leaders of newly formed churches (Acts 13:3, 14:23). As part of Jesus’ Sermon on the Mount, Jesus looks to fasting, along with prayer and almsgiving, as important aspects of piety, but the focus should be on authentic repentance, an interior conversion with the acts done with humility. (Matthew 6:1-18).

As recorded in the Didache, one of the earliest Church documents outside of the New Testament from the 1st century AD, fasting was a weekly activity practiced on Wednesdays (in memory of Jesus Christ’s betrayal) and Fridays (to mourn the crucifixion of Christ) in contrast to the Jewish custom of Mondays and Thursdays. A fast before the reception of the sacraments of Baptism and Holy Communion was common too. Over time, with the formulation of a Lenten season, fasting would take on an especially important role then. However, as noted by Irenaeus in the 2nd century, debates still existed at his time not only over the dating of Easter, but when and how long a fast before Easter was to be undertaken – a day, two days, or more. The early Church saw fasting as a form of disciplining the body while also focusing the mind on God. Tertullian, from the 2nd century too, wrote on the origins, significance and types in On Fasting. During the 4th century, there is written evidence showing that Athanasius encouraged his flock to fast during what was then becoming a more formally recognized Lenten season of around forty days.

The nature of the fast seems to have varied too. One historian from the 5th century known as Socrates (not to be confused with the philosopher) reported that some would basically only eat bread or vegetables during the fast period, while others would eat dairy and/or fish. Overall, the general practice seemed to be to eat one meal only on a fasting day in the evening with meat and wine excluded entirely during the Lenten fast.

As time went on, it was recognized that the obligations were too strict in general application and needed to be adapted to handle various practical situations. Actually some of the first exceptions began within monastic communities around the 9th century where some of the monks performed hard manual labor during much of the day. Thus the concept of “collation” emerged whereby a small amount of food, not as a meal, was permitted after mid-day. Some of the Catholic military orders associated with the Crusades era were exempt from fasting rules too. The age of industrialization increased the importance from a safety perspective more than anything else for workers to remain mentally alert and physically active for long periods during their daily work shift. So as we approached the present day, increasing relaxations were made in both reducing the number of fast days and the obligations to be met with regards to the nature of the fast.

For today’s Catholics, an obligatory fasting day now consists of one full meal with up to two small meals that do not equal a full meal also permitted. There are no specific rules on when the meals are taken and liquids are allowed at any time. A fast is required by those 18-59 years old on Fridays in Lent, except if there is a Solemnity coinciding with one of those days. On Ash Wednesday and Good Friday, those 14 and older are obliged to avoid meat altogether, but fish and other seafood are permitted. Exemptions are made for those 60 years or older, sick or have some other medical condition that makes the obligation difficult, pregnant and nursing women, and other legitimate reasons. A one hour fast, with the exception of water and medicine, before receiving Holy Communion is also obligatory.

Something perhaps overlooked today by many is that fasting days by the faithful are encouraged basically whenever deemed appropriate as an individual seeks some spiritual restoration or guidance. It is still recommended to abstain from meat on Fridays throughout the year, but it is not an obligation as other penitential acts such as prayer and works of charity can serve the same intended purpose. As noted in Mark 9:29, Jesus himself points to the supernatural power that comes from fasting. He said in response to a healing he performed that his disciples could not do despite being able to perform many other healings that sometimes an evil can only be overcome through a combination of prayer and fasting.

Apparitions – How does the Church discern them?

As we conclude the month of May (the month of Mary), we will address perhaps another area of intense scrutiny and debate: the validity of apparitions and what exactly that means for the Church membership as a whole. Read on to learn more.

The Church’s Catechism teaches that the fullness of revelation was achieved with Jesus Christ. Thus public revelation ended with the teachings Jesus either shared publicly or privately with His Apostles who in turn shared it publicly as they embarked on their missionary work. (see Catechism of the Catholic Church (CCC) 66). This is different from private revelation, which the Church has recognized as ongoing through the centuries. It is under the category of private revelations that various apparitions and other supernatural events fall under. However, it is important to understand that private revelation does not offer anything new to the deposit of faith (CCC 67). Consequently, when the Church officially recognizes an apparition either at a local, regional or universal level, there is no obedience of faith required of the Church membership.

With that said, one may wonder how does the Church go about “approving” apparitions and other reported supernatural activity? The Church actually just recently released updated norms on how to investigate these situations, the first update since 1978. The Church has always looked at supernatural reports with scrutiny in order to assess their legitimacy. The evaluation process has proven in many cases to be very slow (ie: decades with only six cases officially resolved since 1950), which was a point of concern brought up in the recent guidelines. Another point of concern was the confusion sometimes caused by permitting the bishop of a diocese to issue a verdict about an event being “supernatural” or “not supernatural” without an official recognition of approval by the Dicastery for the Doctrine of Faith, which is in charge of religious discipline in the Church. Consequently questions over whether the faithful are obliged to believe in the event sometimes to the point of valuing it beyond the Gospel itself have occurred.

The new norms basically outline the 6 conclusions that can be reached after an investigation, ranging from a declaration that the event is not of supernatural origin to authorizing and promoting piety and devotion associated with a phenomenon. The decisions made by the local bishop must be signed off by the Dicastery as well. A definitive “supernatural” declaration is no longer to be made as the intentions now are to emphasize the fruitfulness associated with an approved event, while not suggesting there is an obligation on the part of the faithful to believe in it. The hope is that this strategy will help speed up decisions as there is not the definitive declaration of “supernatural” or not necessary, which takes very intense/lengthy investigations along with the ramifications of such a decision possibly being proven false in the future. The Pope reserves the right to step in though to declare something supernatural, but that exception has rarely been utilized in recent centuries.

It should be noted that many of the shrines today associated with alleged supernatural events have never really been officially declared as such by the Church, but rather the result of a sensus fidelium (sense of the faithful). One of the few cases of official approval concerns the Sanctuary of Our Lady of the Rosary of San Nicolas in Buenos Aires (see photo), which was built in response to Marian apparitions primarily during the 1980s to a woman living in the city. The supernatural origin of the apparitions was not formally approved by the local bishop until 2016. Perhaps with these updated norms some of the backlog of ongoing investigational proceedings can attain an official decision by the Church Authority more quickly.

The Rosary (Part 2)

Victories at Muret and Lepanto

Having touched upon the historical development of the Rosary recently, we now turn to some of the miraculous events associated with it. A complete summary is certainly not possible here but two “rosary victories” – one in France in 1213 and the other on the coastline of Greece in 1571 – are worth highlighting in particular. Read on to learn more.

Not long after St. Dominic’s Marian apparition concerning the rosary, a pivotal military battle was held on September 12, 1213 that changed the course of the conflict between Albigensianism and Catholicism. Near the city of Toulouse at Muret in southern France, an army of an estimated 20,000 or more representing the Albigensian movement met a Catholic Crusader army of only around 1,500 men. The story goes that the much larger army being confident in the impending victory spent the night before battle drinking and revelring, while the much smaller army prayed the rosary. Mass and confessions were heard early in the morning before St. Dominic retreated to the Church of Saint-Jacques in Muret to continue prayers. The Catholic army then proceeded from the town to meet the opposing army, successfully routing the disorganized and hung over army. Catholics in the area quickly attributed the victory to the intercessory role of Mary from the Rosary. The Battle of Muret represented the last major battle of what was known as the Albigensian Crusade with the heresy subsiding and a peace treaty eventually signed in 1229.

Moving forward to the 16th century, another battle which many say changed the course of European history had strong connections with the Rosary. The Protestant rebellion of this time had led to a very divided Europe. At the same time, another religion, Islam, was flexing its military muscle in the East with the expansion of the Ottoman Empire. In the previous century, Muslims had seized control of Constantinople, which had served as the center of Christianity in the East going back to the time of Constantine the Great in the 4th century. They then started chipping away at parts of Eastern Europe, even attempting (unsuccessfully) to take Vienna in 1529. In another siege involving a town in what is today Montenegro (near Serbia), the citizens were told to pray the Rosary. In the end a Muslim army of 30,000 men frustratingly left after unsuccessfully taking the town. This was just a precursor of what was to come.

Another siege on the island of Malta in 1565 between a Catholic force of 6,000 and a Muslim armada of 40,000 saw the Catholic force successfully defend the island under its commander who had a specially made sword with the rosary engraved on it. However, the Muslim forces regrouped and began having more success, taking Cyprus and other islands near the coastline of Greece, progressing closer to Rome and amassing a fleet of 300 war ships and 100,000 men by the fall of 1571. Pope Pius V, sensing the gravity of the situation, had been attempting to form a Holy League of nations to counter the Muslim advances. But with Europe divided, only Spain and Venice (a separate nation state within Italy) responded. A fleet with a little over 200 ships and 70,000 men was assembled in Naples, Italy. The pope assigned a devout Catholic from Austria, only 24 years old, named Don Juan, to command the fleet. Don Juan commanded his men to refrain from swearing and fast for 3 days as part of preparations. Female visitors on the ships were not permitted and he gave a rosary to each man to pray. Likewise, the pope urged groups of people across Italy to join in praying the rosary.

On October 7, 1571 the Christian fleet faced a headwind, which was a huge disadvantage at a time when war ships were rowed by either slave labor or the fighters themselves, as they approached the port of Lepanto, Greece where the Ottoman Turk force was anchored. The two sides met in battle with reporters of the event conveying that the Christian fleet positioned itself in the shape of a cross while the Muslim fleet formed a crescent moon. The battle immediately favored the Turks and the situation looked dire for the Christians until inexplicably the wind changed directions giving the Christians a huge change of fortune. In the end, the Christian forces lost around 12 ships while the Muslims over 200 ships. As victory was just at hand and before news could ever reach Rome, the pope had a premonition announcing the victory. Pope Pius V would go on to establish the Feast of Our Lady of Victory, now known as the Feast of Our Lady of the Rosary on October 7. While another major advance would be attempted by the Ottoman Turks on Vienna a little over 100 years later, the battle at Lepanto (see picture) goes down in history as being instrumental in Europe’s defense against Muslim military advances.

The Rosary – Crown of Roses

Perhaps one of the more misunderstood sacramentals of the Church by those unfamiliar, the development and utilization of the Rosary by the faithful spans across most of the history of the Church. Was it simply given to St. Dominic through a Marian apparition as some traditions would lead you to believe? What’s with the repetitive prayers? Like most stories, there is certainly more to understand. For more on the major milestones along the way, read more here.

The practice of repetitive prayers is as old as the Church, being an important component of monastic prayer life in particular. There is a written account concerning Paul the Hermit (c. 227-c.341, yes he lived to be 113 years old!), where he would toss a pebble into a pile each time he said one of three hundred Our Fathers daily. Repetitive prayers served as a form of penance. Of course the impracticality of carrying a bunch of pebbles around led to other forms of counting, such as cords and then beads. Eighth century Irish monks are credited with the origination of what became known as Paternoster beads, consisting of 150 beads to represent the 150 Psalms in the Bible. While the prayer life of the monks involved the reciting of the Psalms, those you had difficulty reading and/or memorizing them would alternatively say the Our Father. The beads would be worn on a belt or hung around the arm or neck or simply held in the hand.

While initially only Our Fathers were said (or chanted), the practice of saying 150 Hail Mary’s too began to surface around the 11th century, spearheaded in particular by the Cistercians and the Cathusians, who both utilized a Marian Psalter alongside the pre-existing Paternoster Psalter. While the Our Father prayer goes back to Jesus Himself and is recorded in the Gospels of Matthew and Luke, the contents of the Hail Mary developed over several centuries. However, the first part of the Hail Mary is Scriptural as well, a concatenation of the Angel Gabriel’s salutation to Mary at the Annunciation (Luke 1:28) and Elizabeth’s greeting of Mary at the Visitation (Luke 1:42) which produces “Hail, Mary, full of grace. The Lord is with thee. Blessed are thou among women and blessed is the fruit of thy womb.” It was this form of the Hail Mary that appears to be the version used primarily until around the 14th century. More on the subsequent additions to the prayer will be mentioned in a bit.

As founder of the Order of the Preachers (Dominicans), St. Dominic lived in the late 12th and 13th centuries. Despite his great oratory skills. Dominic struggled to win back those who had fallen victim to the Albigensian Heresy of the age, which advocated the existence of 2 Gods – a good God of Heaven and a bad God of the world, essentially a new form of Gnostic heresies that had plagued the Church from its beginnings. As Dominic prayed for help with the challenges before him, he received a Marian apparition where Our Lady instructed him to utilize the Marian Psalter as a preaching tool (see picture). So instead of being the founder of the Marian devotional, Dominic was instructed on using it in a different way centered on reciting the devotional in sections of 10 Holy Marys while meditating on one of the mysterious events in the life of Christ. A total of 15 mysteries were established to cover the reciting of 150 Holy Marys. This new preaching tool proved effective for Dominic and also a pivotal component to some miraculous battle results (more on that in another article). The 15 mysteries would be sub-grouped officially under Pope Pius V during the 16th century into three groups of 5 mysteries each: the Joyful, the Sorrowful and Glorious Mysteries. (Note: In 2002, Pope St. John Paul II would add 5 more mysteries, the Luminous Mysteries, to get to the current 20 Mysteries.) It was also around the lifetime of Dominic that the term Rosary began to be used as an alternative name to the Marian Psalter. The term in Latin, rosarium, refers to a crown or garland of roses. The term would become common in the 15th century, applying to all the various forms of the Marian Psalter, which had also developed in recent centuries.

We now circle back to the formulation of the complete Hail Mary as we know it today.

The remaining parts of the prayer were additions by the Church. Some appear to be just traditions, such as simply adding the names Mary and Jesus within the first part mentioned above. In another case, one can point to the Council of Ephesus in 431, which confirmed the title of Mary as Mother of God towards addressing one of the Christological controversies of that age over the divine and human natures of Jesus Christ and what that meant with regards to Mary’s role in it all. Tradition also holds that Ephesus was the location of where Mary lived for most of the remainder of her life after Jesus’ Ascension and that the villagers were most pleased with the council’s decision that they cried out in the streets “Holy Mary! Mother of God! Pray for us sinners!” However, the official inclusion of this phrase along with “.. now and at the hour of death” seems to have not happened until during the time of the Black Death, a plague in the mid-14th century which ravaged much of Europe, killing around 50% of the population! With death all-around and the significant chance one would catch and die from the disease, this hopeful plea to Mary became especially important to believers.

The Month of Our Lady (May)

The Story Behind this Month Long Devotion to Mary

May is known as the Month of Mary. Perhaps some may think it has to do with the similarities in the names of the month and the Mother of God while others may also see an association with Spring flowers and/or the celebration of Mother’s Day in this month. However, there is more to the story. Read on to learn more.

While Mary has always played an important part within the Church, Marian devotion in the Western Church increased around the 11th century. At this time a custom known as Tricesimum (or “Thirty-Day Devotion to Mary”, also called “Lady Month”) developed locally/regionally and was originally held from August 15-September 14 perhaps to align with the Feast of the Assumption of Mary, which does currently reside on August 15. The intent was to perform a spiritual exercise, such as a recitation of the Rosary, on each day within the 30 day period.

A more widespread practice toward a month-long devotion to Mary in May occurred in the 18th century when Jesuit Fr. Latomia in Rome shifted the focus of a devotional month for Mary to May. It is believed it was initially an attempt to increase the piety of his students and focus attention on the true Faith while turning away from other ancient pagan-rooted cultural practices. For many cultures, May was typically a time associated with the beginning of new life and the full arrival of Spring. Fr. Latomia’s practice spread to other Jesuit educational institutes and parishes, and was supported by the popes.

While there are no required rituals to be performed during the Month of May concerning this month-long devotion to Mary there is often a “May Crowning” event performed where a statue of Mary is crowned with typically a crown of flowers (see picture), which harkens to the Coronation of Mary as Queen of Heaven, which is celebrated as a feast day on August 22. There are some feast days though within the General Roman Calendar in May which are focused on Mary. The feast day for Our Lady of Fatima is celebrated on May 13. It recalls the series of six, once-a-month Marian apparitions to three shepherd children in Portugal between May 13-Oct 13, 1917 which culminated with the miracle of the dancing sun in the sky witnessed by thousands. May 31 is also the feast day for the Visitation when upon receiving news from the angel Gabriel concerning the conception of Jesus by the Holy Spirit, Mary traveled to her cousin Elizabeth and stayed with her for three months. It should also be noted that depending on when the Easter Season falls in a given year, there is often the Feast of the Blessed Virgin Mary, Mother of the Church in May as it falls on the Monday after Pentecost. This feast day was recently added by Pope Francis to the General Roman Calendar in 2018.

As we continue within the month of May, next time we will review the origins of one of the most important sacramentals of the Church, which is also deeply associated with Mary, the Rosary.

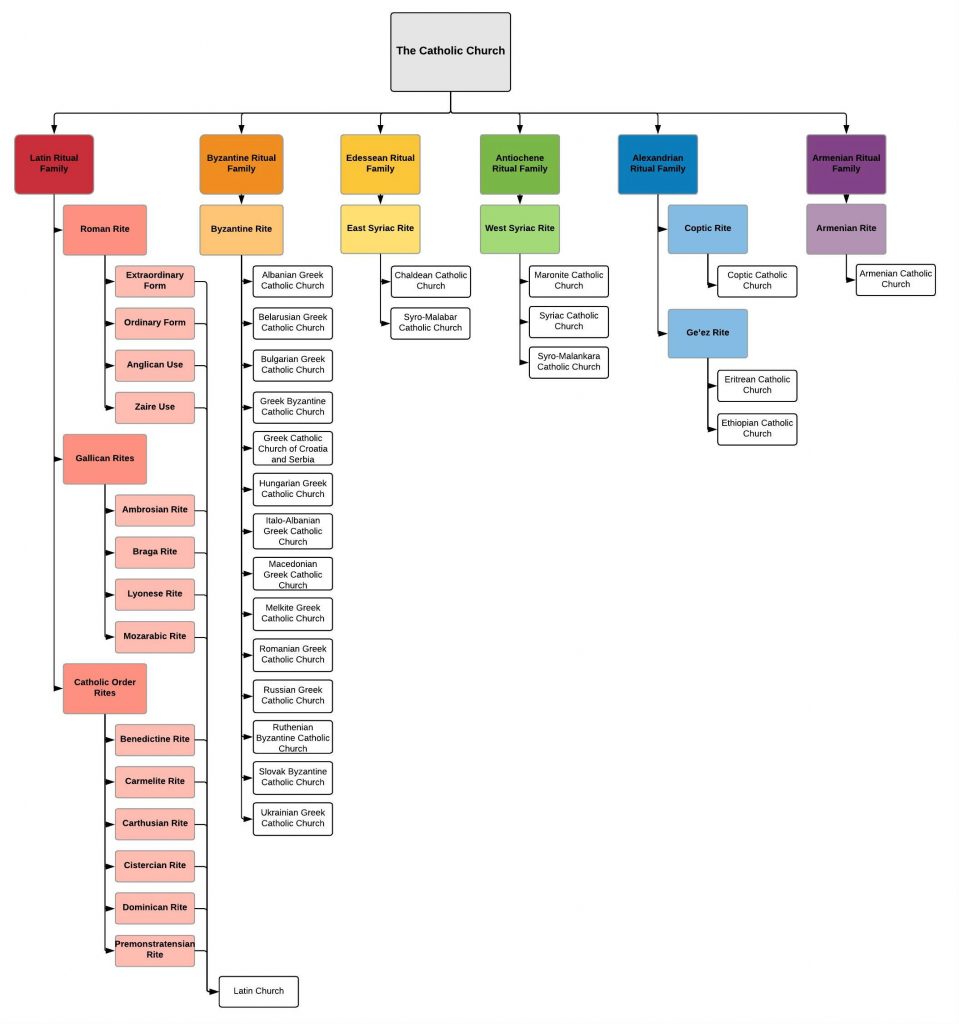

Catholic Liturgy Around the World – The Rite Stuff

For the majority of Catholics in the West, we are accustomed to following the Latin (aka Roman) Church’s rite of liturgy, but the Latin Church is just one of twenty-four self-governing Churches in full communion with the Pope which make up the Catholic Church. Across these Churches there are six liturgical rites: five reside among Eastern Churches and one resides in the Western Latin Church. Read more for a brief history on these different rites.

(Note: Click on each rite’s header link if desiring to learn more.)

Shortly after the Ascension of Jesus Christ, the Apostles and their disciples began the mission of spreading the Good News to all of the world. Peter journeyed north of Palestine to Antioch (the southernmost part of present-day Turkey) and served as bishop there for a few years before journeying to Rome. Antioch would operate as the center for the establishment of what would become known as the Antiochene Rite. While a Liturgy of St. Peter does exist, this rite is rooted instead in the Liturgy of St. James (first bishop of Jerusalem), originally said in Greek and then translated to Syriac and Arabic. This rite is followed by the Maronite Catholic, Syriac Catholic and Syro-Malankara Catholic Churches. The Eucharist is usually received through intinction where the bread is dipped in wine before being received, a common practice with Eastern Rite traditions. With the exception of the Maronite Church, most Churches of this and the other Eastern rites will confer all three sacraments of initiation (Baptism, Confirmation, and Eucharist) at the same time too, both for adults and infants. Additionally many Eastern Churches have traditionally permitted married men to be priests but not bishops.

Mark the Evangelist, one of Peter’s missionary companions and writer of one of the four Gospels, which is believed to be based on Peter’s recounting of the words and events of Jesus Christ, established the Church in Alexandria, Egypt. Serving as first bishop, he wrote down in Greek what became known as the Liturgy of St Mark. This liturgy was translated to Coptic by St. Cyril of Alexandria in the early 5th century. This liturgy along with one formulated by St Basil in the 4th century primarily make up the Alexandrian Rite still used to this day by the Coptic Catholic Church, Ethiopian Catholic Church, and the more recently established Eritrean Catholic Church, which was separated from the Ethiopian Catholic Church under Pope Francis in 2015. All three Churches offer the Eucharist through intinction. The Coptic Catholic Church uses leavened bread while the other two use unleavened bread.

The Apostles Jude and Bartholomew are believed to have first brought the Christian faith to Armenia (north of present day Iraq and Iran). While during the early centuries the Church in Armenia was under the authority of the bishop of Antioch, language and geographic barriers eventually saw the evolution of a new rite that incorporated parts of other rites with credit given to Gregory the Illuminator. Like the case with the Latin Rite, only one particular Church, namely the Armenian Church, uses this rite. After AD 451, the Armenian Church was separated from Rome over Christological differences concerning the two natures of Jesus Christ until reunification became permanent again in 1740. The rite uses unleavened bread like the Latin tradition, but is the only liturgical tradition where water is not added to the wine. In modern times, most Armenian Catholics are in countries such as Lebanon (see picture of Cathedral in Beirut), the US, Canada, and France as various religious, political, and economic obstacles have compelled many Catholics originally from Armenia to relocate over the last century.

The Apostle Thomas may have been the farthest traveling Apostle of Christ as traditions hold he made his way to areas of Mesopotamia (present day Iraq) and parts of India. From his initial evangelization work sprouted two Churches – the Chaldean and Syro-Malabar Churches. Both Churches also split away from Rome during the 5th century over Christological differences but part of both rejoined in the 16th century. Given distance, the Syro-Malabar Church in India was somewhat forgotten until the age of exploration brought European Catholics in touch with Indian communities that called themselves St. Thomas Christians. After some initial Latinization of liturgical rites, a push occurred to return to the historical rites of the Church. While the Syro-Malabar Church is a thriving Church (second largest Eastern Catholic Church and the source of many religious vocations), the Chaldean Church struggles to survive given the long running Islamic military pressures that exist within Iraq.

Byzantine (Constantinopolitan) Rite

Consisting of 14 particular Churches (mostly named after countries or ethnic groups of Eastern Europe), this Eastern rite is based on the Liturgy of St. John Chrysostom, who was extremely influential as both a bishop and exceptional homilist around Constantinople, the capital of the Eastern Roman Empire (present-day Istanbul, Turkey), during the early 5th century. The rite is something of a merging of the Alexandrian and Antiochene Rites. Sts. Cyril and Methodius are highly revered within Byzantine traditions for their efforts in bringing the Christian faith to many parts of Eastern Europe. Essentially one Byzantine Church existed until after the Great Schism between the Eastern and Western Church unfolded in 1054. Although disagreements had existed for centuries prior and continue to this day between East and West over topics such as the use of leavened vs. unleavened bread, a modification made to the Creed that the East thought was improperly approved, and the authority of the Pope compared to other Patriarchs in the East, this formal schism led to the formation of the Orthodox Church. However, various groups with specific national/ethnic ties would break from the Orthodox Church and rejoin in full communion with the Catholic Church as they saw a need to strengthen ties with the Catholic Church during the time of the Protestant Reformation.

Latin Rite

With the Great Schism between the Eastern and Western Churches in 1054, the Latin (or Roman) Church continued on with an approach that favored a more uniform operational unit. With the fall of the Western Roman Empire in the 5th century, Europe was left for centuries without any central government like had existed under the Roman Empire. The Church oftentimes served as one of the few stabilizing cohesive entities for that period in time. Consequently, only one particular Latin rite Church existed. However, this did not mean that other Latin-based rites did not exist. For example the Gallican Rites, including the Ambrosian Rite of Milan, the Braga Rite of Portugal, and the Mozarabic Rite in parts of Spain, were essentially Latin translations beginning around the 5th century of some of the aforementioned Eastern Rites. Additionally there were Catholic Order Rites, which were specific to certain religious orders, such as the Benedictines, Carmelites and Dominicans. One of the decrees to come out of the reform directives of the Council of Trent (1545-1563) was to solidify the Roman Missal and consequently led to its strict application across the entire Latin Church. However, rites that had existed for at least 200 years for some communities, such as the aforementioned, were permitted to continue.

Incense – Odor of Sanctity

Perhaps for most people the first recollection as a child of frankincense would be as one of the gifts the magi brought to the Nativity of Jesus Christ or the smoky (and smelly) stuff used sometimes at Mass. But what exactly is frankincense and why is it something that plays an important part in the sights and smells of Catholicism?